How to Tell the Difference and Choose the Right Surface Finish

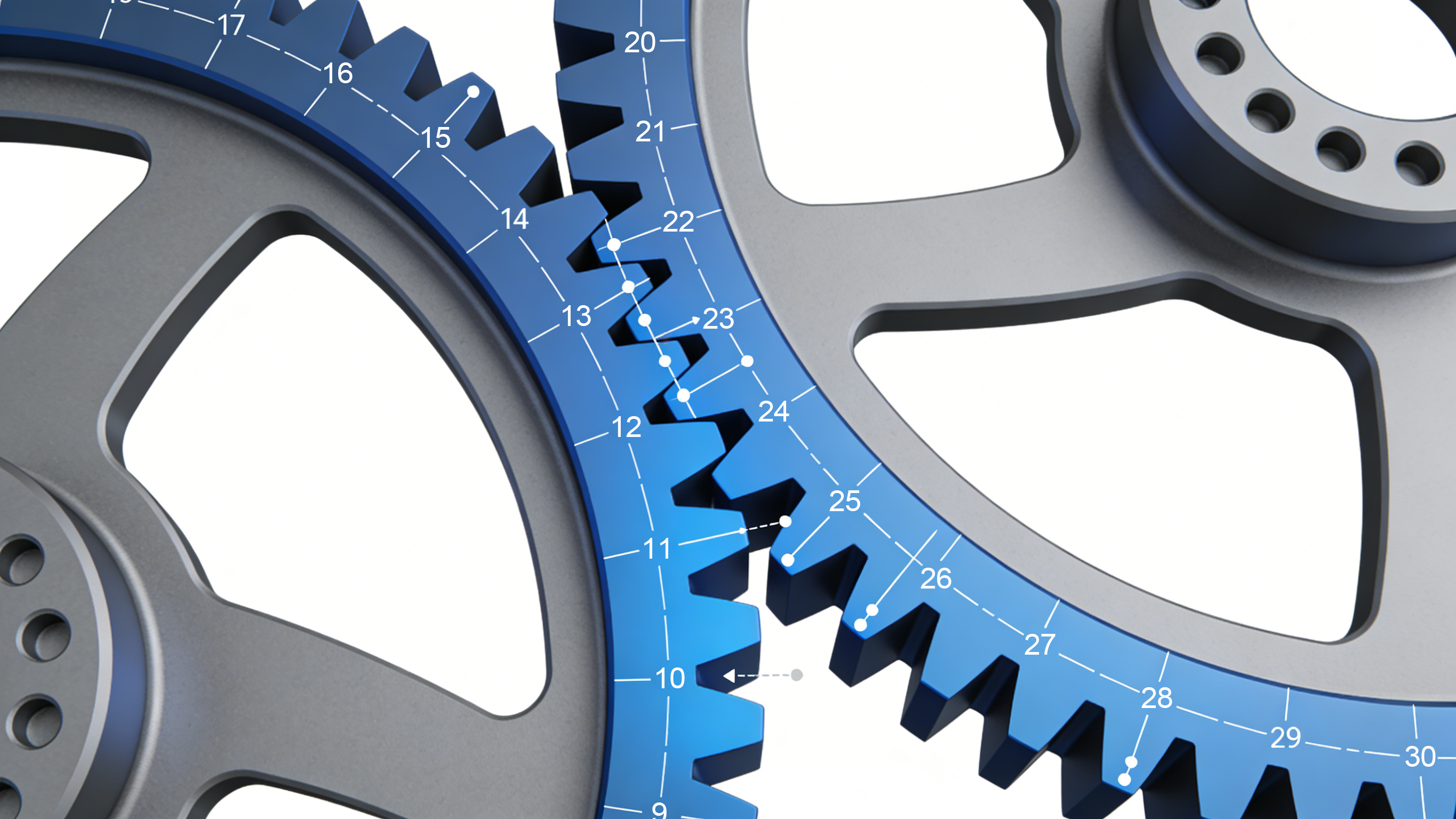

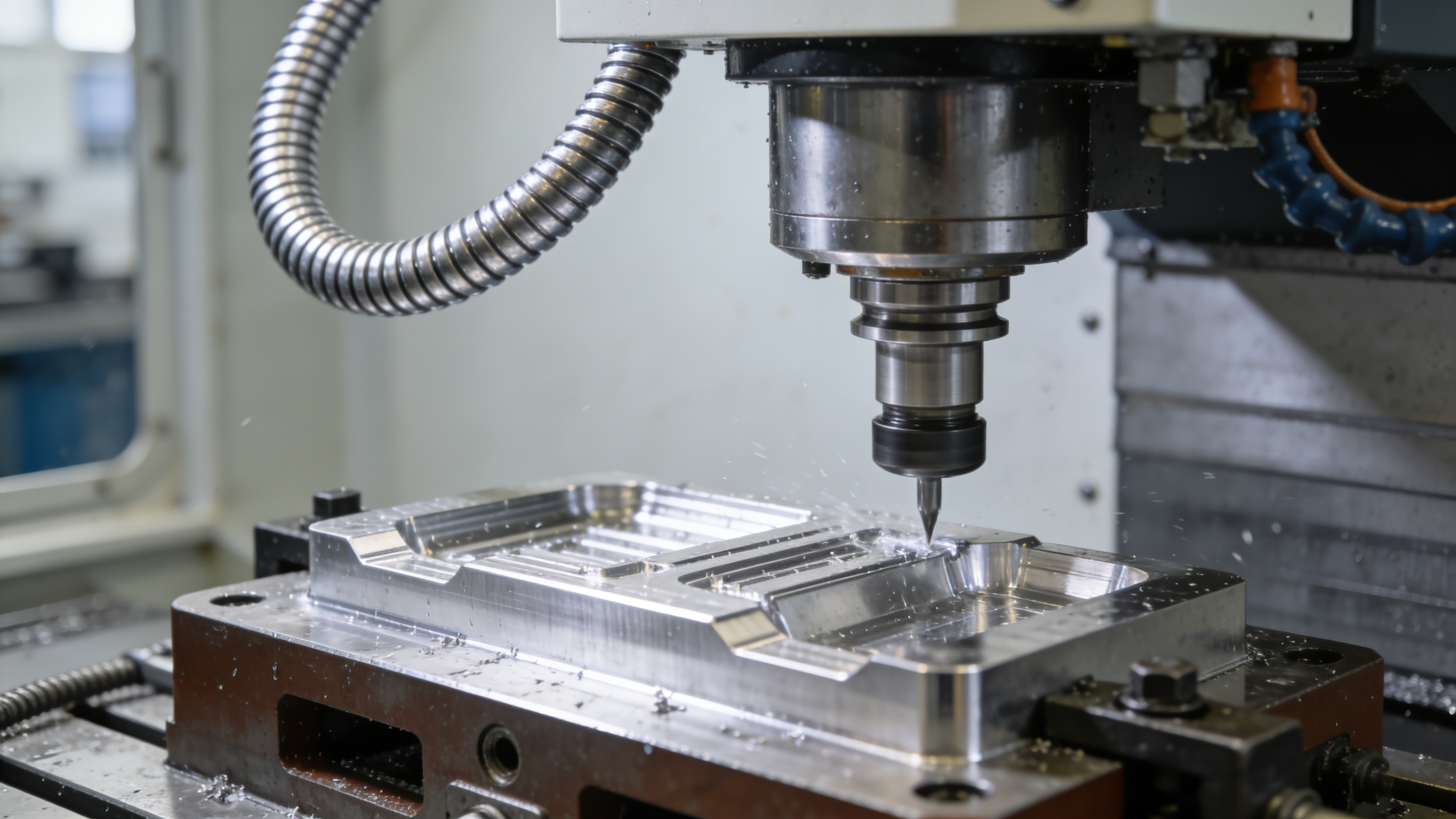

In CNC machining and metal part manufacturing, Black Oxide and E-Coating are two surface finishes that are frequently confused.

Many customers request “black oxide” during the RFQ stage, but after reviewing the material, application, and performance requirements, the correct solution is often E-Coating.

This confusion is widespread — and understandable.

Both finishes can look similar, but their principles, applications, and performance are fundamentally different.

This article explains how to clearly distinguish Black Oxide vs E-Coating, and how to choose the right one for your parts.

This article explains:

- What Is Black Oxide?

- What Is E-Coating (Electrophoretic Coating)?

- Black Oxide vs E-Coating: Key Differences

- Why These Two Finishes Are Often Confused

- How to Choose the Right Finish

- A Simple Question That Avoids Costly Mistakes

- Conclusion

What Is Black Oxide?

Black Oxide is a chemical conversion process, not a coating.

Instead of adding material to the surface, black oxide reacts chemically with the metal to form a thin black oxide layer.

Typical materials

- Carbon steel

- Alloy steel

- Tool steel

Key characteristics

- No measurable thickness buildup

- Minimal dimensional change

- Matte black appearance

Main purposes

- Light corrosion resistance (usually combined with oil or wax)

- Reduced glare

- Improved appearance for precision steel parts

⚠️ Important note

Traditional black oxide is designed for steel materials only.

When aluminum or stainless steel is described as “black oxide,” it is usually a different process with a similar visual effect, not true black oxide.

What Is E-Coating (Electrophoretic Coating)?

E-Coating is a coating process, not a chemical conversion.

Using an electric field, charged paint particles are deposited evenly over the surface of the part and then cured to form a continuous protective film.

Typical materials

- Aluminum alloys

- Steel

- Stainless steel (with proper pretreatment)

Key characteristics

- Uniform coating thickness

- Excellent coverage on complex geometries

- Smooth, consistent appearance

Main purposes

- Strong corrosion resistance

- Improved durability

- Decorative and functional protection

Because black is the most common color used, many customers casually refer to black e-coated parts as “black oxide,” which leads to confusion.

Black Oxide vs E-Coating: Key Differences

| Feature | Black Oxide | E-Coating |

| Process type | Chemical conversion | Coating deposition |

| Typical materials | Steel | Steel, aluminum, stainless steel |

| Thickness | Negligible | Measurable coating layer |

| Corrosion resistance | Light (with oil) | High |

| Appearance | Matte black | Uniform black (often semi-gloss) |

| Dimensional impact | Minimal | Slight |

Why These Two Finishes Are Often Confused

In most RFQs, customers are not describing a process — they are describing a requirement:

- “I want the part to be black.”

- “I need corrosion protection.”

- “The tolerances are critical.”

- “The cost needs to stay reasonable.”

The intended function is correct, but the surface finish name may not be.

Once the material changes, the correct surface treatment often changes as well.

How to Choose the Right Finish

Instead of starting with the finish name, start with these questions:

- What is the base material?

- Is corrosion resistance critical?

- Are tight tolerances involved?

- Is appearance or durability more important?

General guidance

- Choose Black Oxide for precision steel parts where dimensional stability matters

- Choose E-Coating when corrosion resistance and uniform coverage are required, especially for aluminum or complex shapes

A Simple Question That Avoids Costly Mistakes

Before quoting, we often ask:

“When you say black oxide,

do you mean a chemical conversion finish,

or simply a black, corrosion-resistant surface?”

Clarifying this early helps avoid rework, delays, and unexpected costs.

Conclusion

Although Black Oxide and E-Coating may look similar, they serve very different purposes and are suited for different materials and applications.

Understanding the difference helps engineers, purchasers, and manufacturers communicate more clearly — and select the right finish from the start.

If you are unsure which finish fits your part, confirming the function first is always the best approach.